This series of blogs and the release dates are as follows:

AUTISTIC SOLUTIONS RELATED TO TAKING IN INFORMATION

Part One: Using Words to Make Pictures (January 13, 2023)

Part Two: Using Words to Describe Pictures (February 10, 2023)

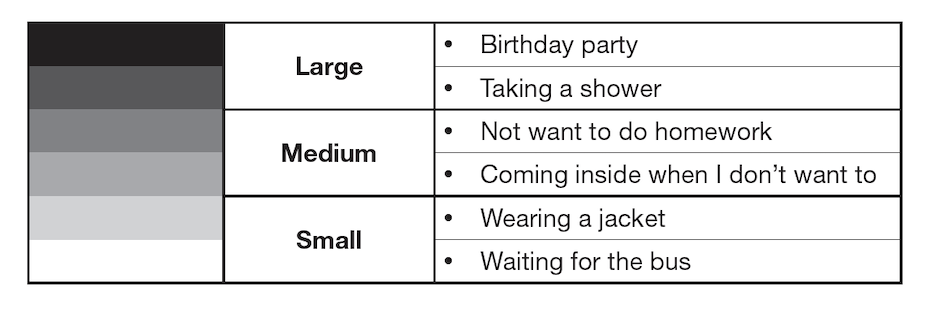

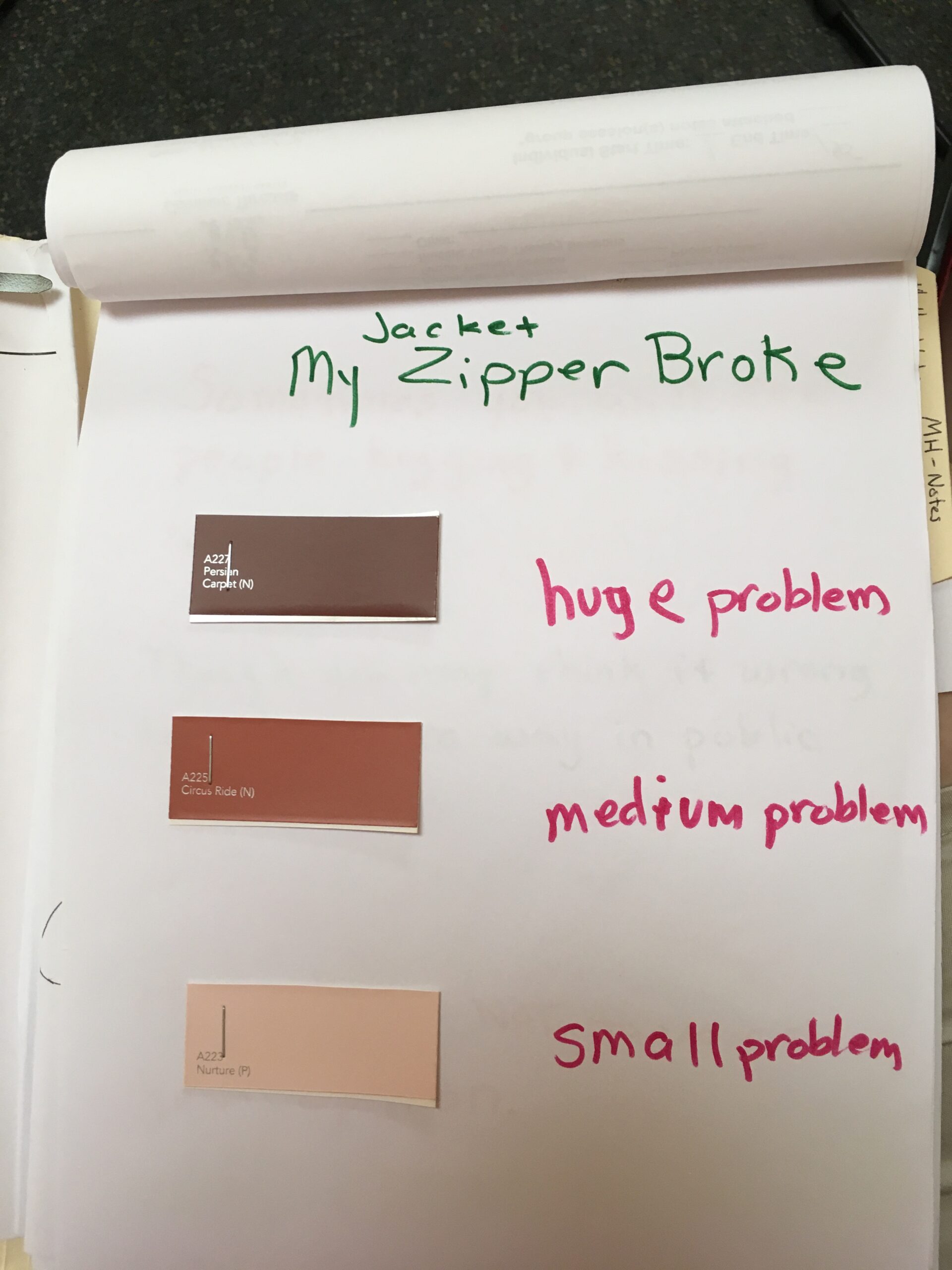

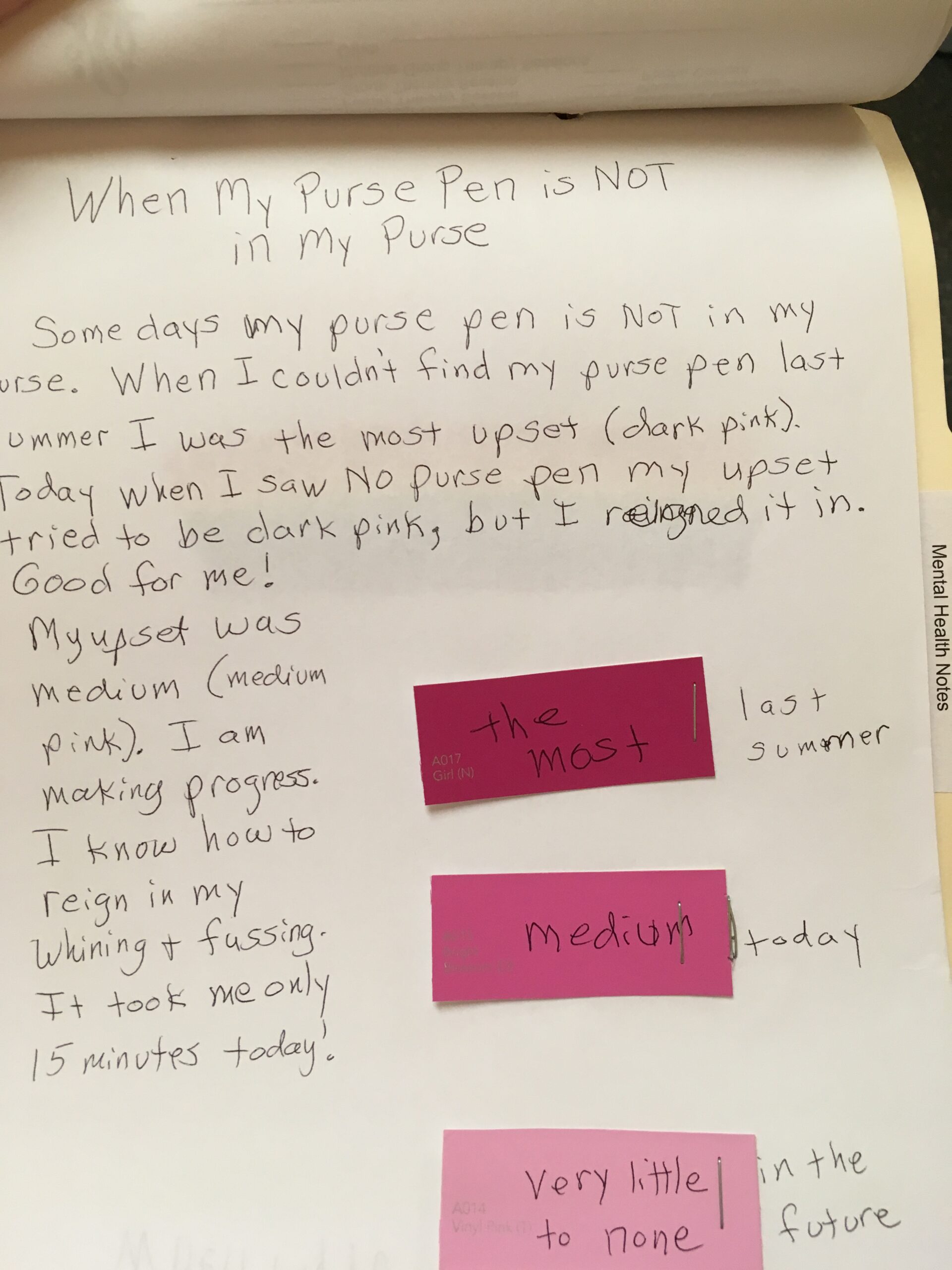

Part Three: When Feelings Are Too Big (March 10, 2023)

Part Four: Examples Using Paint Chip Visual Supports (April 7, 2023)

Part Five: Direct Instruction of Social Information (May 5, 2023)

I would like to tell you a story. It took awhile to sort it out. The support worked because it was in line with the neurology of this client I will call Shelby.

I once worked with a young lady who experiences intense feeling that come on quickly whenever her neurology is hit with a surprise. Remember, a neurological surprise is not necessarily a practical surprise.

This young lady, even though she knew she was soon to leave the house to come see me, when her mom said, “Time to leave. Let’s get in the car,” Shelby’s neurology was hit with this surprise because she hadn’t been tracking the time. This meant Shelby’s fight or flight survival instinct was triggered and she yelled, “No, I’m not going!” while throwing objects and crying. This often made her late to places she was going.

For Shelby, it made sense to teach her how to track time when she needed to leave the house. This prevented the intense feeling from happening. Since Shelby always carried her cell phone with her she received direct instruction along with deliberate practice on setting the timer to go off five minutes ahead of leaving time. When the timer went off she had a few minutes to stop her activity, gather her purse and get to the car.

There are undoubtedly more ways to manage big feelings than there are clients who struggle with them! Our own creativity as clinicians can shine here. I have had many clients who have come to manage their own intense feelings that, in turn, allow them more options in their lives. Some of them learn a few feeling labels along the way and for others the labels that go with their feelings still elude them. Please don’t get stuck on teaching your clients to label their feelings at the expense of helping them learn to manage their feelings.

Direct Instruction of Social Information

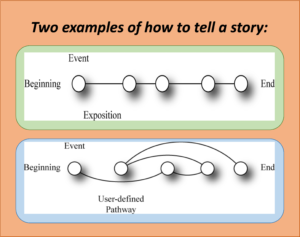

Just like autistics often need direct instruction and practice on how to make their own pictures in their heads when reading a book so that they can comprehend what they are reading, they also often need direct instruction and practice when it comes to learning social rules. Because of autistic brain function, no matter how many times an autistic is in a given situation where others would automatically learn the expected social skill, his brain will have great difficulty being able to identify the social skill and to then use it going forward.

For autistics the social information simply doesn’t get automatically uploaded into the brain as it does for neuromajority people. This social information that we expect one another to know is called the hidden curriculum. Most of the time it is the most important information when it comes to getting along in the world. The hidden curriculum social information often needs to be directly taught to individuals with autism.

This has nothing to do with cognitive ability, but instead it has to do with the brain’s inability to consistently pick up and apply social information in such a way that it becomes part of their very being as they go forward in life. For example, most very young children generally learn that if you want to have a friend to play with it is more likely to happen when you are friendly, share your toys, and take turns when playing a game. Autistic children often need direct instruction and many times of practice to learn these socially expected behaviors.

For one example using direct instruction to teach a client how to be a good loser when playing a game please refer to the blog Autism, Direct Instruction and Having Friends.

Selection from: Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension,

ConversationalEngagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life

Based on Autistic Neurology, pg. 144-145.

Note: The author is a mental health therapist and is also autistic. She intentionally uses identity-first language (rather than person-first language), and invites the reader, if interested, to do further research on the preference of most autistic adults to refer to themselves using identity-first language.

If you are a clinician and interested in learning more about therapy with the autistic client please join me along with two of my colleagues in an online course.

CLICK HERE for additional information about Mental Health Therapy with the Autistic Client.

BY JUDY ENDOW

Endow, J. (2021). Executive Function Assessment. McFarland, WI: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2019). Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology. Lancaster, PA: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the Hidden Curriculum: The Odyssey of One Autistic Adult. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2006). Making Lemonade: Hints for Autism’s Helpers. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2013). Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2009b). Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2009a). Outsmarting Explosive Behavior: A Visual System of Support and Intervention for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2010). Practical Solutions for Stabilizing Students With Classic Autism to Be Ready to Learn: Getting to Go. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Endow, J., & Mayfield, M. (2013). The Hidden Curriculum of Getting and Keeping a Job: Navigating the Social Landscape of Employment. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.