Mental health diagnosis and treatment has evolved over time according to what makes sense and what works for most people. We have an increasing body of research around mental health issues that informs us today. However, when it comes to autistic people we do not have a body of research that informs us about diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders. Autistic people are not like most people. This means we need to understand the underlying autism neurology along with its impacts in the realm of diagnosing and treating mental health disorders in clients also diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Autism is an Operating System

As a clinician it is important to understand that autism is much more than a diagnosis. Autism is a way of being. It is like being blind in that we cannot separate the blindness from the person, but the blindness – or in this case, the autism – defines the person. As an autistic I see, experience, interact with and give back to the world as an autistic. Autism is my operating system. It defines me.

Autistics have a different operating system than typical people. This is not good or bad. It is just different. Think of PlayStation and Xbox gaming systems. Some gamers prefer one to the other, but most gamers like owning both. This is because some games can only be played on PlayStation while other games need an Xbox system. Neither gaming system is good or bad. They are just different systems.

The majority of the people in the world, because they represent the biggest number, are defined as “typical” and we can say they have a typical operating system. Those with autism are in the minority. They are not wired with a typical operating system. Instead they are wired autistic.

Medically and diagnostically speaking, anything not typical is atypical. This is most of the time helpful, but when it comes to autism it has not proven to be very helpful. Most of the times in the medical field when atypical can be changed into typical this is a good thing so that is the goal whenever feasible. Thus, for years we have tried to change autistic people (whom we assumed to be atypical) into typical people by trying to make them behave like typical people. In the process we have learned that we cannot change the operating system. Autistic people have an autistic operating system.

When Clinicians Don’t See the Autism

Today, autistic people, just like the population at large, find their way to therapy when symptoms of depression, anxiety, OCD and other diagnoses become problematic to them in their daily lives.

As clinicians we need to understand the autistic operating system – in other words, to see the autism – if we are to be helpful to our autistic clients. When we do not have a strong grasp on this the results are that our clients are not served well. Clinicians without a good understanding of autism generally sort things out in one of two ways:

- It’s All the Autism

When a client has been previously diagnosed with ASD it is common for mental health clinicians to attribute all psychiatric symptomatology to the autism, which often results in autistics not being diagnosed or treated for comorbid mental illnesses when warranted.

- Can’t See the Forest for the Trees

Another example is our clients who have multiple psychiatric diagnoses for which none of the typical treatments have been effective in lessening symptoms. These clients’ individual symptoms are sometimes collectively better known as autism, but because the autism hasn’t been recognized we miss the boat in rendering effective treatment.

Conclusion

When clinicians do not have a good understanding of the autistic operating system they tend to lean toward one of the two above examples, neither one being helpful in supporting therapeutic progress of autistic clients. The Autistic Operating System, Part Two will delve further into this topic. Stay tuned in this is an area of interest.

(Note: In my practice I see clients who happen to be autistic. Their autism is usually not the reason they seek therapy, but it certainly affects how the therapy for their depression, anxiety or other presenting symptoms is delivered. When mental health therapy is delivered in a usual manner and not based upon the autistic operating system of the client it generally is not very effective.)

BOOKS BY JUDY ENDOW

Endow, J. (2019). Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology. Lancaster, PA: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the Hidden Curriculum: The Odyssey of One Autistic Adult. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2006). Making Lemonade: Hints for Autism’s Helpers. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

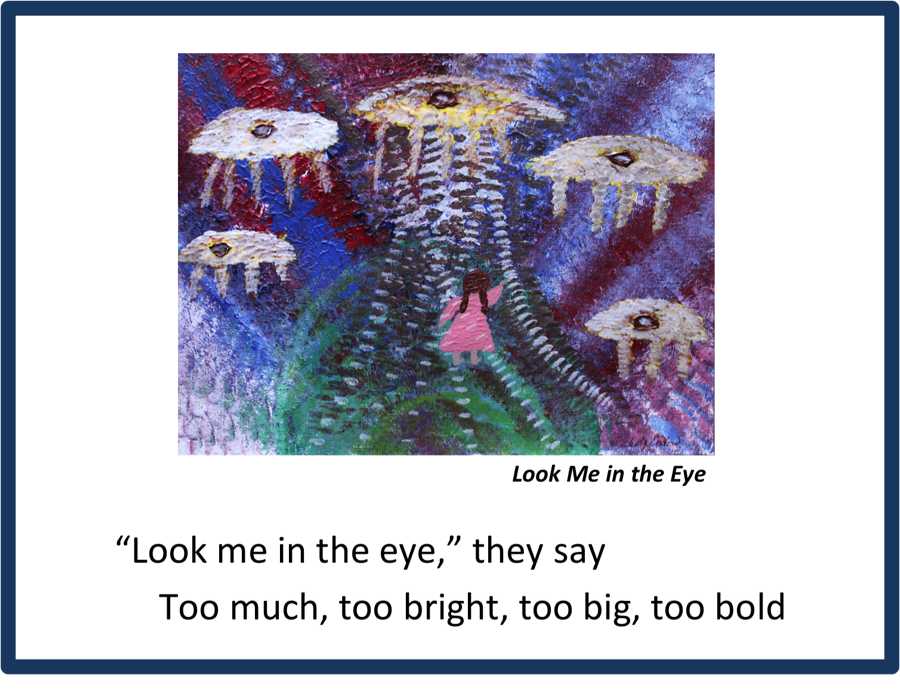

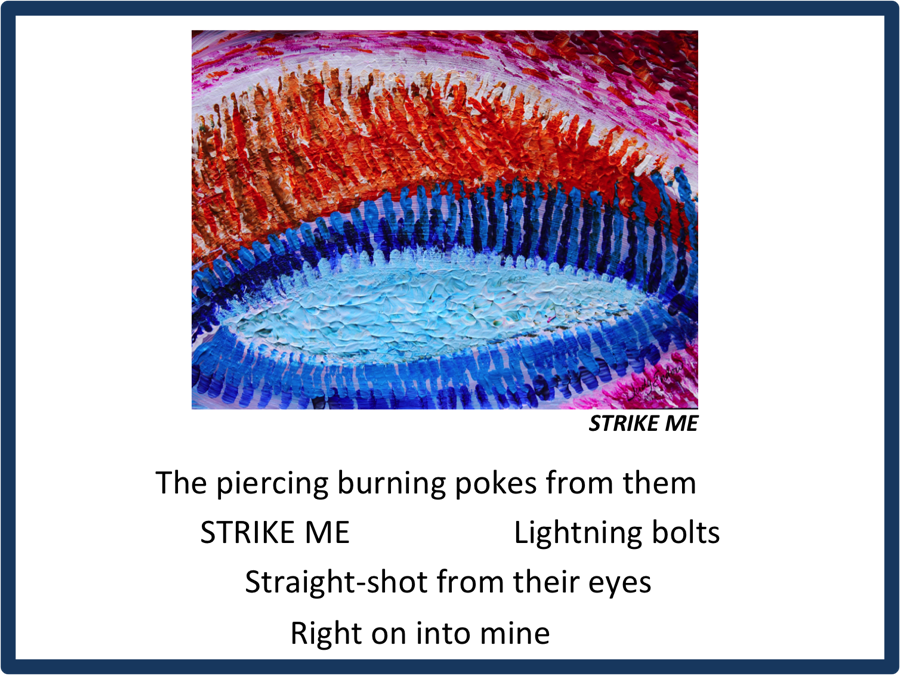

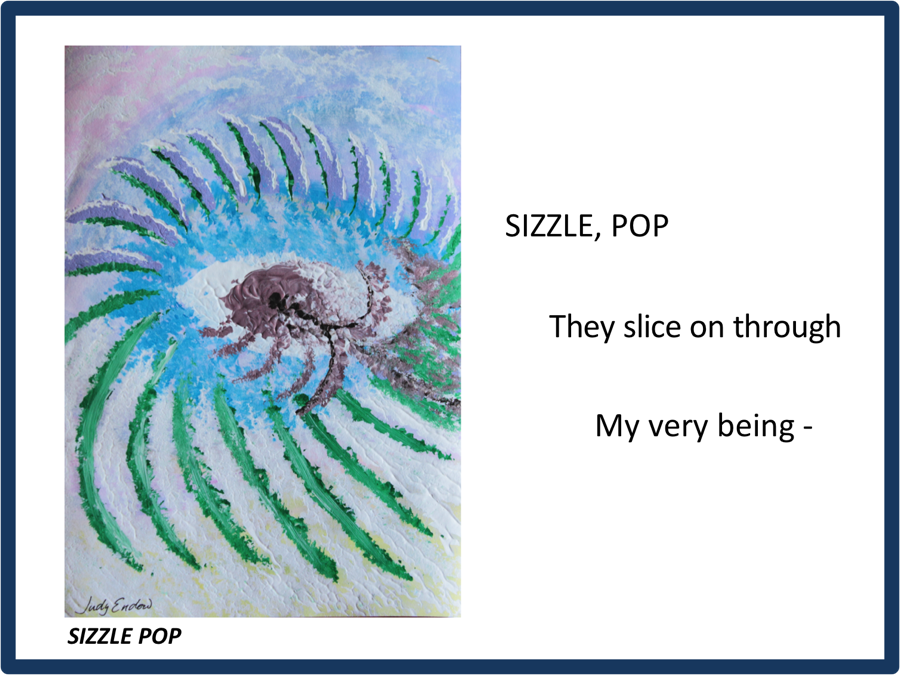

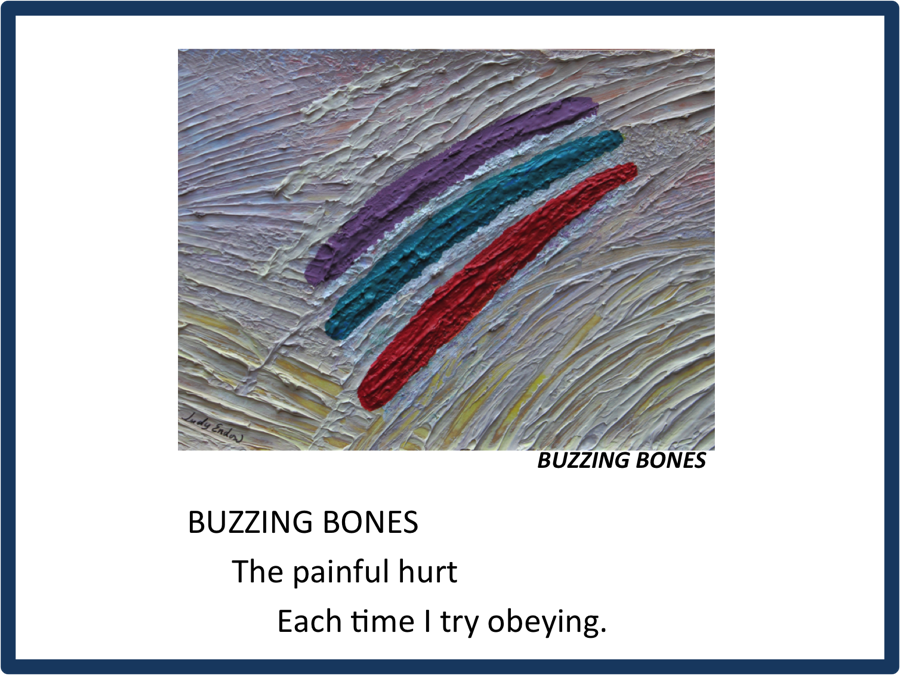

Endow, J. (2013). Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2009). Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2009). Outsmarting Explosive Behavior: A Visual System of Support and Intervention for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2010). Practical Solutions for Stabilizing Students With Classic Autism to Be Ready to Learn: Getting to Go. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Endow, J., & Mayfield, M. (2013). The Hidden Curriculum of Getting and Keeping a Job: Navigating the Social Landscape of Employment. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Originally written for and published by Ollibean on May 4, 2017

Click here to leave comments.