This is the second part of a blog series with this outline

Part One: Creating Pictures in Layers With Two Take and Make Visual Examples

Part Two: Changing or Replacing a Layered Picture With One Take and Make Visual Example

Part Three: Creating, Changing and Replacing Pictures Conclusion

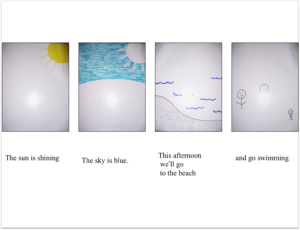

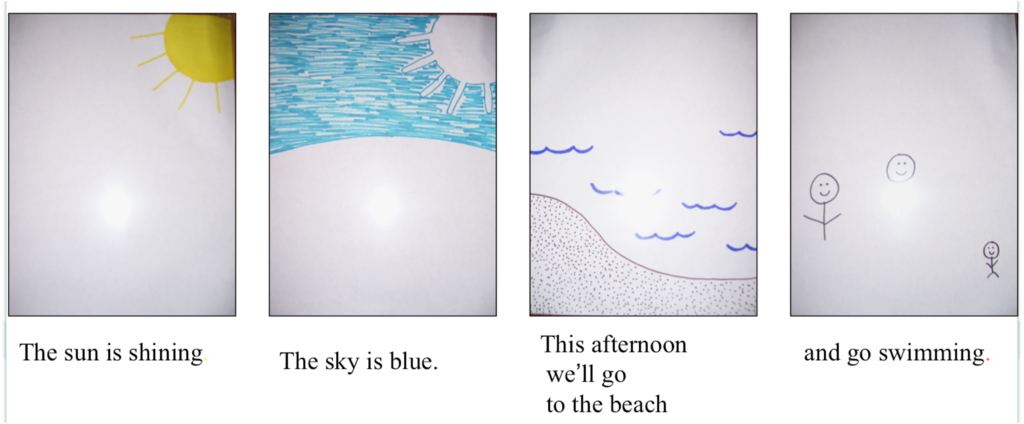

The two stories in Part One of this blog actually happened with a mom and her three children. In the morning the children went to day care at the university where their mom was taking a morning class. When they left the house in the morning the sun was shining, the sky was blue and they were intending to go to the beach for a swim in the afternoon. Most days this worked well. Some days it didn’t because it rained in the afternoon.

For most children, seeing the rain would inform them that they would not be able to go to the beach. The understanding that the beach is closed and that swimming doesn’t occur when it is raining is part of the hidden curriculum – the unspoken social information that neuromajority brains automatically pick up. For individuals with autistic neurology the brain does not always support this automatic understanding of hidden curriculum. Instead, it must be directly taught. When a person is a visual thinker it is no problem at all to simply add raindrops to the picture in their head and consequently see one’s self swimming at the beach in the rain! Thinking in layers allows for the underlying explanation to be made visual, and thus, in an autistic neurologically friendly way to receive and understand the information.

When this mom announced, “We can’t go to the beach because it is raining,” two of her children, though they were unhappy, understood the situation automatically even though nobody had ever told them that people don’t usually go swimming when it is raining or that swimming pools and beaches close when it rains. The third child, having autistic neurology that did not support the synthesis of new information (It is raining) along with the social understanding the beach closes when it rains, reacted to this change of plans. He promptly started screaming, sobbing and was unable to be consoled as he thrashed about in his car seat all the way home while his brothers implicitly understood that even though they would rather go to the beach, they would need to play indoors that afternoon.

I have made and used the two stories from Part One of this blog series and have found them helpful to show autistics of all ages the way the system of thinking in layers works. Some need no further instruction. Once they see the system they can start thinking that way. Most need more practice with the system by using clear overheads to draw out the layers of their visual thinking.

The way I work with this is to first get the story from my client by drawing stick figures and using words. I like to do this using sticky notes. Many of my clients are not able to tell their stories in chronological order. Using sticky notes allows for rearranging the time line of events as needed. Once the sticky note story is in order the drawing it out on overhead projector sheets is easily accomplished.

I usually make explicit the one to one correlation, picking up the first sticky note and drawing that layer on the first overhead projector sheet. Then, placing the second overhead projector sheet on top of the first one and picking up the second sticky note, the second element of the story is drawn. This continues on until all elements of the story are completed. Then, you can identify the one layer that changed, remove it, place a new overhead projector sheet on the top of the story and draw in the new element.

For some the ability to transfer the visual system of thinking in layers to their own internal thoughts happens automatically during the process of working with the external visuals. For others, more explicit support is needed to get the system internalized. With these clients I sometimes prompt each step of the way saying, “Can you see this layer in your head?” or, if needing to be more direct, “Put this layer in your head. Tell me when it is there.” Others don’t need the explicit step by step prompts, but instead I will talk about how this system can work both on the outside by drawing on the overhead projector sheets and on the inside by visually thinking of and stacking up the layers.

Clients have reported a variety of ways this has coalesced for them. For example, one client reported that whenever she felt like everything changed she immediately “layered it up.” This meant the entire visual picture in her head was layered simply by her thinking to layer it up. This allowed her to go through each layer looking for the one layer that had changed. Rather than throwing out her entire picture, she removed the one element, inserting the one new element of change.

Changing a Picture or Replacing a Layered Picture

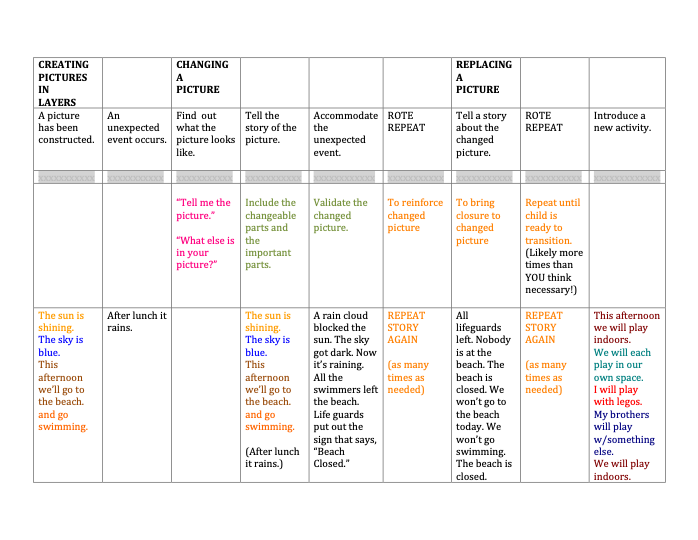

After some practice I came up with an effective protocol to use with clients for changing a picture. This has worked well with clients of all ages and across settings. Below are the steps to the protocol with the example of the Going to the Beach story (introduced in Part One of this blog series) that is in the mind of the autistic and then, when it is actually time to go to the beach it is raining outdoors, meaning that going to the beach will no longer be able to happen that afternoon.

Changing or Replacing a Picture Protocol

1. Construct initial picture in layers (example: Going to the Beach story)

2. Unexpected event occurs (example: It is now raining.)

3. Find out what the picture looks like. You might say things like,

“Tell me our plans” followed by

“What else is in your picture?”

(Example: In this case the little boy had not added anything to the original story. It is important to find out because if building a sandcastle had been added to the story then it can be included going forward when repeating the Going to the Beach story.)

4. Tell the story of the current picture.

Include the important parts

(Example: If building a sandcastle had been added to the original story it is now important and needs to be added in the telling of the story. If no additions occurred then you would tell the original Going to the Beach story.)

Include the changed parts

(Example: If the child had added stopping at the treat hut for a slushy on the way from the beach to the car then this changed item would be added into the original Going to the Beach story. If no changes have been made then the original story stands.)

You will tell this story so that you are both sharing the same story. Once that is the case you will move along to the next step.

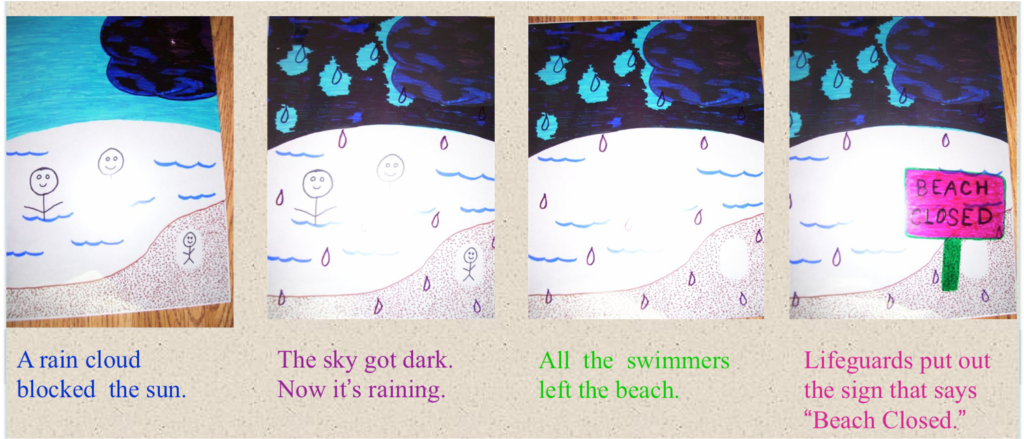

5. Accommodate the unexpected event with a transition story.

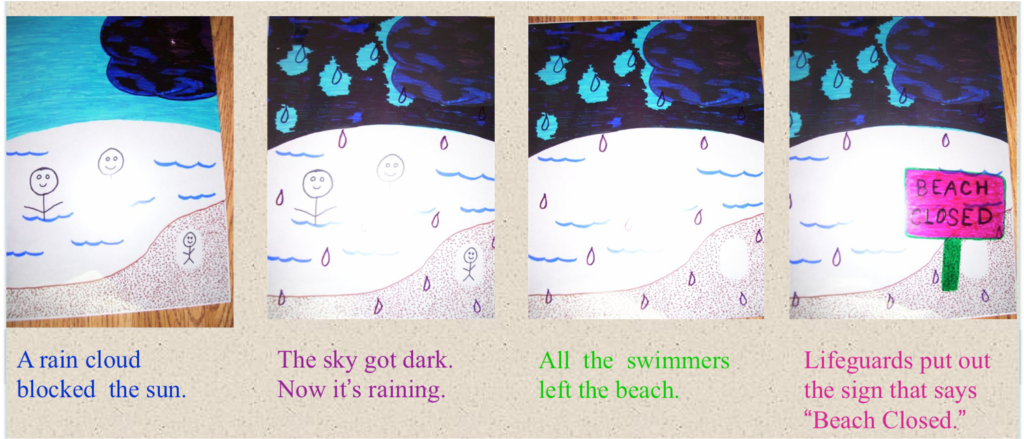

(Example: Because the autistic brain does not automatically synthesize information that may impact the original Going to the Beach story you will need to support this. Here is an example of how to support making changes to the original picture by using the information that it is now raining. Use the layered picture from the Going to the Beach story as the base. Add these elements layer by layer on top of the original overhead stacked story in this order:

-

-

- A raincloud blocked the sun. (Place on top of Going to the Beach layers.)

- The sky got dark. Now it is raining. (Place on top of previous layer.)

- All the swimmers left the beach. (Pull out the layer showing the swimmers.)

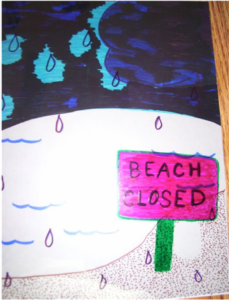

- Lifeguards put out the sign that says, “Beach Closed.” (Place on top of previous layer.)

You will want to ascertain this story of the unexpected event is in place. You can tell part of the story and prompt the child, “Tell me what’s next.” Repeating this in a rote manner several times is helpful. Once he knows the whole story you can take turns telling it.

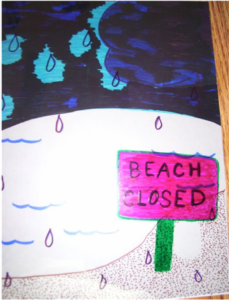

6. Tell a story about the changed picture to reinforce the changed picture and then tell the story some more to help the child bring closure to the original story of Going to the Beach.

Example: In this case “the beach is closed” is the salient line. Simply saying that you are not going to the beach would likely not be concrete enough. Tie in a concrete feature of the unexpected event.

Story 3

Transition Story

-

-

-

-

-

- The lifeguards left.

Nobody is at the beach.

The beach is closed.

- We won’t go to the beach today.

The beach is closed.

- We won’t go swimming.

- The beach is closed

The transition story will need to be repeated until the child is tired of the it and ready to transition to something different. Only then is the child ready for the new activity able to be introduced. Talking about the new activity too soon will hit the neurology as a surprise and may precipitate a meltdown.

7. Introduce new activity

(Example: Playing Indoors story (introduced in Part One of this blog series.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you are a clinician and interested in learning more about therapy with the autistic client please join me along with two of my colleagues in an online course.

CLICK HERE for additional information about Mental Health Therapy with the Autistic Client.

Note: The author is a mental health therapist and is also autistic. She iintentionally uses identity-first language (rather than person-first language), and invites the reader, if interested, to do further research on the preference of most autistic adults to refer to themselves using identity-first language.

This blog series is based on Chapter 9 from Autistically Thriving:Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology, pg. 126-133.

BY JUDY ENDOW

Endow, J. (2021). Executive Function Assessment. McFarland, WI: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2019). Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology. Lancaster, PA: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the Hidden Curriculum: The Odyssey of One Autistic Adult. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2006). Making Lemonade: Hints for Autism’s Helpers. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2013). Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2009b). Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2009a). Outsmarting Explosive Behavior: A Visual System of Support and Intervention for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2010). Practical Solutions for Stabilizing Students With Classic Autism to Be Ready to Learn: Getting to Go. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Endow, J., & Mayfield, M. (2013). The Hidden Curriculum of Getting and Keeping a Job: Navigating the Social Landscape of Employment. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.