My autistic neurology means that I am not good at picking up typical social cues, understanding complex social situations, automatically picking up meanings of idioms, or understanding the hidden curriculum that most others automatically pick up (Endow 2012). This means I often look naïve and gullible. The fact is I AM naïve and gullible when I try to use the social constructs of neuromajority folks to navigate the world around me.

When I was younger and deemed “in need of help” that “help” largely involved others trying to teach me to think and act as if I had a typically wired brain. I was never very good at it because no matter how many therapeutic social skills situations I availed myself of, because they were taught as if all participants had a neurotypical brain and my brain was not neurotypical, I mostly failed their learning agenda for me. My brain just plain works differently.

Here is an example: I rarely remember the same details about other people that most folks do. I remember the visual perception that came to me during an interaction, whether or not I was personally a part of that interaction. I pick up much information through seeing the sounds and movements of color people generate along with changes in the air space surrounding them as they speak and go about their business.

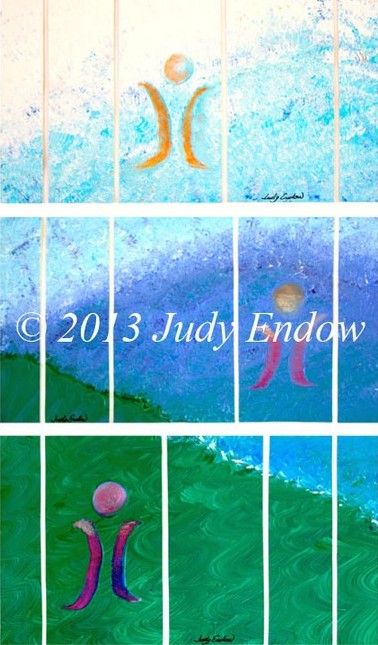

When I match the colors of others I can carry on a conversation. When our colors don’t match, the conversation usually doesn’t go well. I did not realize this way of perceiving and understanding the essence of people was not shared by others until recent years (Endow, 2013).

All through my life when others have tried to help me it has been minimally helpful to me. They would most often try to get me to understand the world in the way they understand the world. It was helpful information to know how others were thinking because it explained their behavior. Even so, learning how typical people think does not help me to then be able to think in their way.

Now that you have read the above example of one way I think visually by incorporating the sound and movement of colors people generate do you understand it? Probably so. And now that you understand how I think can you stop thinking the way you think and start thinking the way I think? Probably not!

The way we think is important because it is how we make decisions. It is part of everyday life. In my work life I might avoid business interactions with someone because they have ugly colors with sticky tentacles moving sneakily toward me. A typical person, who’s thinking is language-based, may understand that this potential business partner is devious and less than ethical in his practices. In essence, we both understood the same thing, but I had no way to explain it unless I translated my visual thinking into words. Visual is my native language; it is how I interface with the world around me and how I innately understand people.

Just like it would not be helpful for you to adopt my ways which are foreign to you, please understand that it is not helpful for me to always adopt your foreign ways when making decisions about people. We think differently and that is okay with me. I look forward to the day that my way of thinking is okay with the rest of the world.

In the meantime, if you are a parent of an autistic child, perhaps you might find it useful to ponder these questions:

- Do you know how your autistic child remembers people?

- Do you know what is important to your autistic child about other people?

- Do you understand how your autistic child decides who to interact with and who not to interact with?

- Do you honor this, even if you may not understand it? Many autistic children will not be able to explain to you how they think because it is not word based. You do not necessarily need to understand how your child thinks in order to honor it.

Note: Here is my first attempt to translate my visual thinking on the essence of people. After I translated my visual thinking into this sketchy language I was then able to go the next step to make a paragraph of words (which is the indented paragraph above that starts with “Here is an example”}. This is how my visual thinking gets translated to words. Once translated to words I can then speak the words. Today I can do this three-part translation

- visual thought,

- sketchy words,

- paragraph words

to be able to speak my thought. I didn’t know until recently that most people do not need to do a three-step translation before speaking their thoughts. Most of the time these days, after decades of practice, my speaking appears quite fluid, though sometimes a delay is still apparent. It is often hard to translate because the world of English words is much more limited than my visual thought. It is like being confined to a limited choice board when what I really want isn’t an available choice.

The Essence of People

Melodious sounds

From your

Colors

Are music

To my ears

Or not

The patterns

Of swirls

Of the colors

Of you

Emanate

From your being

When matches

I make

I can

Conversate

We connect

My soul

With yours

Beyond words

But if not

Then

I can’t

Leaving

You to be you

And

Me to be me

Each

In

The essence

Of

Our

Being

(Endow, 2013)

BOOKS BY JUDY ENDOW

Endow, J. (2019). Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology. Lancaster, PA: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the Hidden Curriculum: The Odyssey of One Autistic Adult. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2006). Making Lemonade: Hints for Autism’s Helpers. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2013). Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2009). Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2009). Outsmarting Explosive Behavior: A Visual System of Support and Intervention for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2010). Practical Solutions for Stabilizing Students With Classic Autism to Be Ready to Learn: Getting to Go. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Endow, J., & Mayfield, M. (2013). The Hidden Curriculum of Getting and Keeping a Job: Navigating the Social Landscape of Employment. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Originally written for and published by Ollibean on July 30, 2015.

To comment on this blog click here.