Many autistic students, who have difficulty transitioning from one activity to another, benefit from using a visual schedule in the same interactive way for each transition. Visual schedules provide the means to implement the same transition routine each time the activity changes. Many teachers simply say, “Check your schedule” to signal when it is time for one activity to end and another to begin. Those words serve to initiate the transition routine which the student has learned to complete once initiated without further prompting.

When getting your student to use a schedule, whether it is a schedule with activities represented by real objects or one where activities are represented by pictures or by words, it is important to be mindful of the prompts you put in for the student. Before introducing anything new, think through how you want the student to ultimately engage in the activity.

- Do you want the student to start only after you verbally prompt him? For example, when a student puts a picture from his schedule into the “all-done” pocket, if you want him to be in the habit of waiting to start the next subject, you would teach him to only start after you prompt him saying something like, “Look what’s next.” Some teachers do this because they need to check over work the student just completed before wanting him to move on to the next subject or task on the schedule, or they may need to get materials for the student to use in the next subject or task.

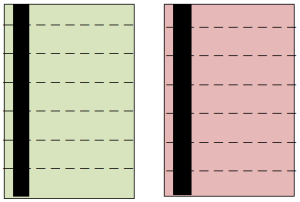

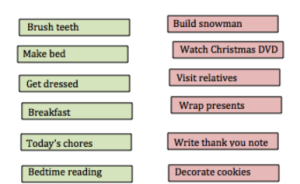

- Do you want one prompt to initiate a whole sequence? It is most expedient to use one prompt such as “Get ready for the bus” to initiate the chain of events that is to occur when getting ready for the bus. Initially, the student may not know what getting ready for the bus entails. What often happens is that someone prompts the student each step of the way so as to offer support and to keep the student on track to ensure he is out the door to the bus on time. As a result, some students inadvertently learn to wait for the prompt each step of the way. To avoid this, it is helpful to provide a mini-schedule of pictures to show each step in getting ready for the bus. Then you can use one verbal prompt “Get ready for the bus” and use visuals for the student to track the process. Remember NOT to insert verbal prompts as you teach the student to follow the mini-schedule.

At the same time, when students are learning to follow the sequence of steps, you may need to repeatedly draw their attention to the visual. One way of doing this without speaking – and inadvertently creating a prompt – is to take the student’s finger, put it on the beginning of the picture sequence, and then when he is looking, move his finger through the pictures that represent steps he has already completed, stopping at the picture showing where he is in the sequence. This designates what he is to do next.

It may take several days or weeks for the student to learn this, but once learned, it will be a lifelong skill as we need to “get ready” for countless things and situations. Visuals can be used for the process of getting ready for several different things, such as getting ready for the day (self-care, getting dressed), getting ready for school (school clothes, lunch, backpack, jacket), and getting ready for bed (pajamas, brush teeth, story book). Adults get ready for work, for taking the car in for an oil change, for grocery shopping, etc. The fact is, we all “get ready” for many reoccurring events. All we are doing for our students is making that process visual, teaching it to them, and setting them up from the outset to be able to accomplish the entire process independently when we tell them, in this case, “Get ready for the bus.”

- Do you want the student to need a prompt each step of the way? Occasionally you may want the student to wait for a prompt for each step of the way, such as on a field trip to a new place where you may not know exactly what will happen when. It then becomes helpful to the student to know that he can count on your prompt each step of the way. At the same time, it is helpful for you to know that the student will not do anything new until you prompt him to do so.

However, in most everyday situations it is not helpful for our students to need to be prompted each step of the way. Most everyday situations are repeated over and over, time after time. Typical students learn from repeated routine that when the teacher says, “Time for math,” she expects students to have their math book, math notebook, and pencil on their desk with everything else put away. However, our students with autism often need to be taught the routine directly as they do not pick up on routines in the same way typical students learn them.

It is natural for us to verbally prompt each step of the process and that is what is helpful and what works for most students. In fact, it works so well that we don’t even realize when we are doing it. Only when we prompt each step over and over more times than typically necessary for most students do we become frustrated. Verbally prompting each step of a sequence isn’t an expedient way for many students with autism to learn routines. In fact, this often results in the teacher exasperatedly exclaiming, “He is sooooo prompt dependent!” Just remember that for every prompt-dependent student, there has been a prompt-dependent teacher – rarely someone who set out to intentionally teach prompt dependency, but who never-the-less has taught his student well!

Often, educational assistants work with students with ASD. Since they often work with only one student, they end up talking to that student a lot, often using continuous verbal prompting in their well-intentioned attempt to be helpful to the student. Unfortunately, many students learn that the way to do any activity is to wait for the prompt each step of the way. In the end, they may not be able to use their visual schedule unless the teacher or assistant talks them through each and every step at every transition from one activity to the next. Before you start using any new visual with a student it is most important to know that visuals do not need to be narrated! In fact, narrating visuals often insures they are not nearly as helpful as they would have been had your verbiage not been inserted.

To avoid such counterproductive outcomes, it is important to think carefully of the prompts up-front, only putting in what is necessary rather than all of a sudden realizing that your student is not able to use his picture schedule unless you are prompting him each step of the way. It can be difficult to fade prompts, so it is best not to incorporate them in the first place. So, plan ahead. What do you want to ultimately happen when you say, “Check your schedule?”

BOOKS BY JUDY ENDOW

Endow, J. (2019). Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology. Lancaster, PA: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the Hidden Curriculum: The Odyssey of One Autistic Adult. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2006). Making Lemonade: Hints for Autism’s Helpers. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2013). Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2009). Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2009). Outsmarting Explosive Behavior: A Visual System of Support and Intervention for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2010). Practical Solutions for Stabilizing Students With Classic Autism to Be Ready to Learn: Getting to Go. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Endow, J., & Mayfield, M. (2013). The Hidden Curriculum of Getting and Keeping a Job: Navigating the Social Landscape of Employment. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Originally written for and published by Ollibean on November 19, 2015

To leave a comment at the end of this blog on the Ollibean site click here.