Sometimes autistic neurology – specifically our style of thinking and the way our brain handles information – bumps up against what can appear to be psychiatric symptomatology. This has happened to me many times over the years. My style of thinking is visual along with being quite literal and concrete. I understand myself and, in general, thoughts, ideas and concepts by having or creating an object or visual representation of that construct. Here is an example:

“…in my life, I have come to a fuller understanding of the parts of me as represented by actual pastel-colored stones. I have the collection in a small box. Each stone holds for me the information about a segment of my history. This is why, as a child, information learned in one setting didn’t automatically transfer to another setting for me, as it seemed to do for others. For example, the “home Judy” might be able to tie shoes and know how to make a sandwich, but the “school Judy” would not be able to access these skills” (Endow, 2009b, p. 17).

In the field of autism, we say individuals are not very good at generalization. We try very hard to help students perform learned skills in a multitude of environments to support generalization. I wonder if we had a way to discover how our student was taking in, processing, storing and retrieving information if we might then be able to develop a system for them to be able to generalize. Once the system was developed would generalization be able to happen? Nobody knows as it hasn’t yet happened, but it is an interesting question.

In the field of mental health we tend to see in Dissociative Identity Disorder distinctly different parts of one person, sometimes the parts seemingly unknown to each other. I was actually diagnosed with this back when it was called Multiple Personality Disorder. Today I believe this historical diagnosis more accurately represents my autistic style of visual thinking in a very literal and concrete way along with the way my neurology takes in, processes, stores and retrieves information.

“Thus, this first pile of stones was comprised of several pastel-colored bits representing the inside unconnected parts of me –

WHO I was

in different places,

much of the know-how of the various WHO’s

unrelated to each other

each WHO of her represented by

a separate pastel bit of colored stone” (Endow, 2009b, p.17).

Illustration of Concrete Thinking Impact

Over time, as I grew from a child to a teenager, and then into the various stages of womanhood, I was able to look back over the lifetime of these pastel stones. Each of them as its own bit of ME recorded and encapsulated into an entity of its own. These pastel stones held my history, each era distinct and separate from all the others, with none of the content of the stones overlapping.

Illustration of Information Storage Impact

No wonder I often felt unconnected to my past, as if I was continually starting my life over! I came to understand that this was a function of the way I processed and stored the happenings of my life – each bit encapsulated in its own entity, never intertwined with any other events. It often felt to me as if I was lost from myself.

Illustration of Information Retrieval Impact

When the content of these pastel stones became available to me in my thirties, I was finally able to piece together my past into one whole. During my forties I was able to think of myself as one whole person with a past, a present and a future yet to come. Today I have a good sense of my own personhood, being able to line up the story of each stone chronologically to tell my history, and also to imagine forward into the future. I do this by thing about what story the next stone will show. I have to be able to visualize a new pastel stone inside me before I can plan something into the future, like an upcoming vacation, for example.

Moving Forward

I think it is important to start discussion the issue of when characteristics of autism in general and psychiatric symptoms in specific may be a reflection of autistic neurology – part and parcel of how one thinks and how one takes in, processes, stores and relieves information. Back then, it was diagnosed as Multiple Personality Disorder, known today as Dissociative Identity Disorder. This diagnosis was not accurate nor was it helpful.

One reason it becomes crucial in teasing out whether we are looking at autistic neurology or psychiatric symptomatology is because autistic neurology need not be fixed. Instead, we all simply need to understand how it works for specific individuals and then, based on individual self-determination, we can proceed. For example. in my life, I sometimes just need to explain how I store and retrieve information when I need extra time to answer a question. Other times I simple say, “Please give me a minute.”

On the other hand, when something is reflective of psychiatric symptomatology, then the supports and treatments available to the general public need to be available to the autistic too. It is not appropriate to attribute psychiatric symptomatology to autism. It is appropriate, however, to treat psychiatric symptomatology of an autistic person through the lens of autism.

Selection from Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology, pgs.43-45.

If you are a clinician and interested in learning more about therapy with the autistic client please join me along with two of my colleagues in an online course.

CLICK HERE for additional information about Mental Health Therapy with the Autistic Client.

Note: The author is a mental health therapist and is also autistic. She iintentionally uses identity-first language (rather than person-first language), and invites the reader, if interested, to do further research on the preference of most autistic adults to refer to themselves using identity-first language.

BOOKS BY JUDY ENDOW

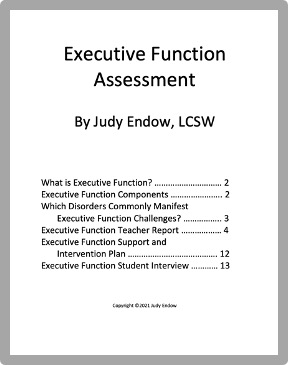

Endow, J. (2021). Executive Function Assessment. McFarland, WI: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2019). Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology. Lancaster, PA: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the Hidden Curriculum: The Odyssey of One Autistic Adult. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2006). Making Lemonade: Hints for Autism’s Helpers. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2013). Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2009b). Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2009a). Outsmarting Explosive Behavior: A Visual System of Support and Intervention for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2010). Practical Solutions for Stabilizing Students With Classic Autism to Be Ready to Learn: Getting to Go. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Endow, J., & Mayfield, M. (2013). The Hidden Curriculum of Getting and Keeping a Job: Navigating the Social Landscape of Employment. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.