I started painting with acrylics in 2012. I wanted to use that medium to illustrate aspects of my autism. To date I have written several articles and books along with speaking in three countries about aspects of autism. Painting is one more way to explain some of the nuances of autism to those who might be interested.

Painting allows me to show perceptions of the world that I see with my eyes as delivered through the neurology of my autism. I match up what I see with the colors and movements of paint on canvas paper. I have not taken classes about painting, other than a one-hour lesson where someone allowed me to watch him paint and ask questions about painting supplies and techniques. I determined after that hour that I could learn to paint.

So, now I paint. I just do it and really do not know if I am doing it correctly or not. What is important to me is the finished product – a painting allowing others to be able to see what I see.

It took me most of my life to realize that what I see isn’t what most other people see. I want people to understand some of the aspects of my autism that I cannot expediently explain with words, but can readily show by painting.

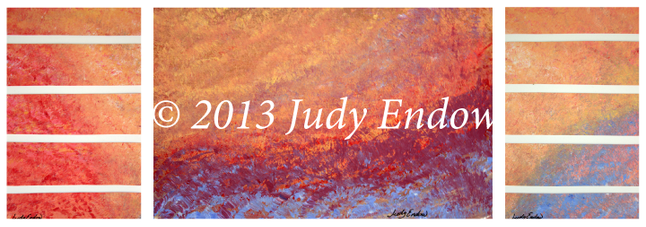

One of those aspects of my autism is something I call fractured vision. It typically occurs when I am in sensory overload. What I am looking at divides up. Imagine a picture that is suddenly cut up into several pieces. One day when this fractured vision phenomena was occurring, I wondered if I might be able to illustrate it through painting.

To illustrate this concept, I copied what was happening by cutting a painting into the pieces my visual perception was delivering to me at that moment. Over the course of a few weeks I took each opportunity of real-time fractured vision as I experienced it and showed what happened by painting and then cutting the painting into the fractured pieces my eyes were delivering to me.

Please know that not all autistics experience the world in the same way I do. The more salient take away point here is that more than 90% of autistics have sensory system differences from the neuro majority population (Baker, 2008 and Baranek, 2006). Those differences impact all of who we are and how we navigate in this world. Because most people don’t experience what we experience there typically are not words adequate to describe it.

When I was growing up, and as a young adult, whenever I would try to describe my experience either it was discounted as not possible, I was said to have a big imagination or it was thought that I was hallucinating. If you want to read more about my story you can do so in the book called Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism (Endow, 2009). From my early 20’s until my late 50’s I refrained from talking about my experiences. It kept me out of psychiatric institutions and that was a good thing.

Today I am braver and I am now in charge of my own life so am able to talk about aspects of my autism without needing to worry what will happen if others do not believe me. At this point in my life others do not have the power to decide my experiences mean I am in need of a psych hospital – at least they no longer tell me this AND even if people would think it, there is no longer anyone who has the power to make it happen. This helps me to be brave and speak out and show my experience through painting.

Here is a picture of one of my paintings I use to illustrate the aspect of my autism I refer to as fractured vision. To see more paintings illustrating fractured vision look in the 2013 Gallery of the Art Store at my website. If you would like to see a larger collection of my paintings along with words explaining the aspects of autism they illustrate please see the book called Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated (Endow, 2013).

Blue Mountain Panorama by Judy Endow

Blue Mountain Panorama by Judy Endow

Note: Greeting cards along with prints in three sizes

available for purchase

at the

Art Store on www.judyendow.com

BOOKS BY JUDY ENDOW

Endow, J. (2019). Autistically Thriving: Reading Comprehension, Conversational Engagement, and Living a Self-Determined Life Based on Autistic Neurology. Lancaster, PA: Judy Endow.

Endow, J. (2012). Learning the Hidden Curriculum: The Odyssey of One Autistic Adult. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2006). Making Lemonade: Hints for Autism’s Helpers. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2013). Painted Words: Aspects of Autism Translated. Cambridge, WI: CBR Press.

Endow, J. (2009). Paper Words: Discovering and Living With My Autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2009). Outsmarting Explosive Behavior: A Visual System of Support and Intervention for Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Endow, J. (2010). Practical Solutions for Stabilizing Students With Classic Autism to Be Ready to Learn: Getting to Go. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Endow, J., & Mayfield, M. (2013). The Hidden Curriculum of Getting and Keeping a Job: Navigating the Social Landscape of Employment. Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Originally written for and published by Ollibean on August 5, 2014